Writer’s Note: The intent of this article is not to slander to any comic book publishers or writers who worked on any of the stories mentioned in this article.

“Don’t be dead Gwen; I don’t want you to be dead!”

-Spider-Man, The Amazing Spider-Man #121

Everyone knows the story. The main, male, protagonist meets a girl and they fall in love. Then, tragedy strikes causing the protagonist to lose the love of his life for the benefit of his character development. However, is it truly just a tool for character development?

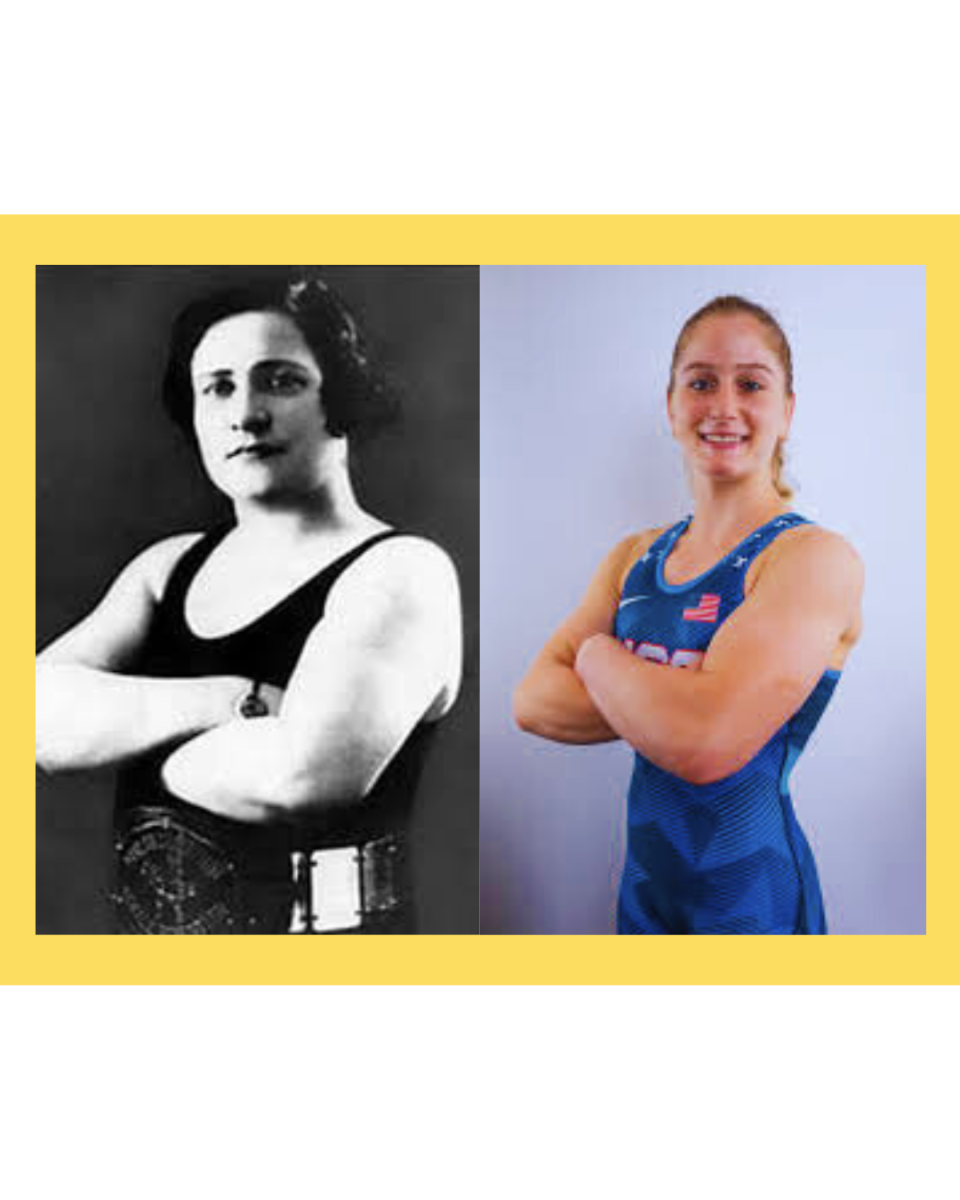

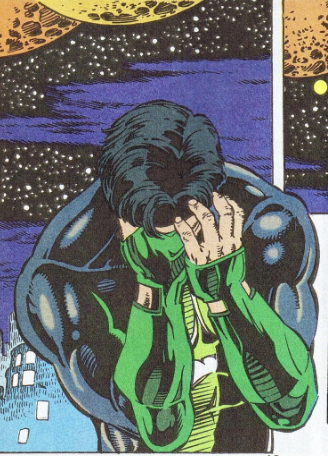

The use of this trope is called “fridging” or “the refrigerator girls” first introduced in 1994 in The Green Lantern, volume 3, issue #54.

(Alyson Banegas)

In issue #54, Kyle Rayner comes back to his home to find his girlfriend, Alexandra, deceased. She was killed by a villain of his and the violence was set in a refrigerator. Thus, the term “fridging” was born.

At first glance, it may not seem like a practice for readers to worry about. This tragic loss of a character is something readers have been exposed to in books, movies, plays, and of course, other comic books. Unfortunately, this practice of “fridging” seems to have readers constantly seeing females placed in violent or deadly scenarios.

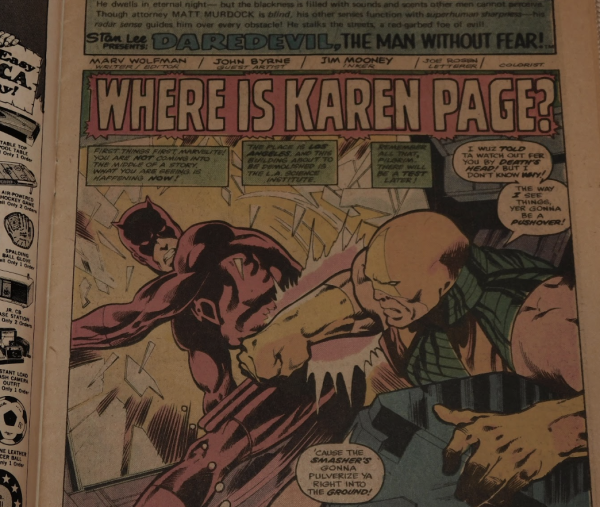

For another example , one particularly impactful incident of fridging is the death of Elektra Natchios, Daredevil’s love interest. More than just a love interest, she is an anti-hero herself; one who even took on the Daredevil title for a while.

In Marvel’s issue #181 of Daredevil, Elektra was killed by the enemy of Daredevil, Bullseye: A villain with the ability to aim accurately with any object.

As with all fridging incidents, her death served to develop the protagonist’s character. Her story became a small part of his story. Instead of remaining the star of her own story, she became a small piece of his story.

It’s important to note that fridging doesn’t have to end with the finality of death. Fridging can range from the disempowering, the assault, or other destruction of a character. In essence, it is the siphoning of one character’s power to another.

Why is this important to consider?

While male main characters often face noble or heroic deaths for the sake of the world, sometimes even for the universe, it’s often the female characters in the story facing the more tragic and hopeless death. In the world of comics, men are tragic heroes. Women are simply tragic.

Readers have recognized this aspect of female character deaths and have discussed the issue in depth on blogs and forums like Reddit. A big part of the overall comic book community agrees that the trope is overall “tiresome,” “sexist,” and “misogynistic.” The author of Green Lantern, Volume 3, Ron Marz, has responded to the amount of backlash he has gotten.

This explanation doesn’t help prove the insignificance of fridging. In fact, it helps explain the very significant impact it has on the world of comics. When women are always the victim, how often can they be thought of as a title character?

The aftermath of a female character’s death is also very different from that of a male character. Two well known DC comic book characters, The Flash and Supergirl, were killed off. They were both title characters. Readers should be able to expect them to be treated similarly. However, The Flash was honored as a hero; another hero took the mantle of The Flash and his comic issues continued. Supergirl was erased from continuity and did not return for over 20 years.

Why is it that the majority of the male heroes are always saving the day while the female characters are going to an early grave?

I had a talk with Mia Robinson, a former student at Central Islip High School, and comic book enthusiast. This is what she had to say about the topic being a female comic book fan herself:

This framing helps us to understand how serious fridging can be, not just to the characters, but more so to the entire community of readers who want to enjoy comic books.

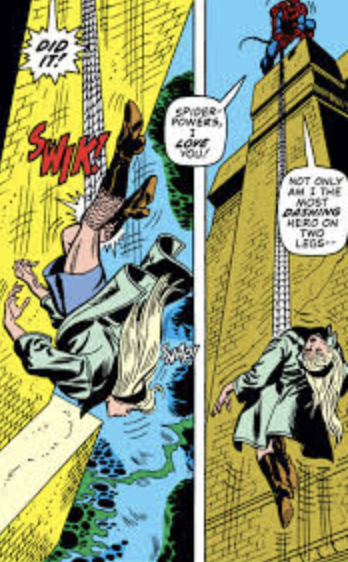

(Alyson Banegas)

How can we stop this “Fridging” trope?

Writers could start by being creative when making their own stories and developing the female character as a whole. They can give them their own sense of character with an actual story and a distinct identity instead of simply making them to be killed off for the protagonist’s pain and character arc.

It’s not overall criminal for a character to die, but we need to be mindful of whether the character is dying for their story or for others.

In conclusion, fridging isn’t only damaging to the fans who enjoy certain characters and enjoy their stories, but damaging to the generation of fans who feel belittled when seeing the character of their same sex constantly being pictured as the victim and the person in constant need of help. Fridge girls are a damaging aspect of the comic book community and we need to do better. We need to hold writers accountable for the impact of their stories. Female characters should not serve solely as the catalyst to tell a story more worthy of being told.